Key Points:

- By blocking or removing CD38 from older mice, researchers raised NAD+ levels, the number of blood stem cells, and the ability of blood stem cells to refresh the immune system.

- Conversely, in young mice, removing CD38 caused blood stem cell numbers to drop in quantity and quality.

- The results point to the importance of NAD+ boosting to optimally improve immune system aging.

Blood stem cells help our bodies repair and grow new tissues all through our lives, and scientists have found a way to keep them from dying off too quickly as we get older. Getting rid of or blocking an enzyme that breaks down NAD+, a molecule important for keeping stem cells young, can stop blood stem cells from getting older, according to a study published in Nature Aging. This study by University of California, Berkeley professor Danica Chen suggests a way to preserve our immune systems and blood stem cells.

Immune system health affects aging

Our immune systems weaken with age. An aging process called immunosenescence makes the immune system and blood quality deteriorate. This process leads to fewer immune cells being made, weaker immune responses, and long-lasting inflammation. These changes make people more likely to get infections, slower to heal wounds, and more likely to get long-term diseases like cancer and heart disease, all of which shorten people’s lives.

Finding out how healthy our immune system is can help us guess how long we will live and stay healthy. Scientists have also used our immune system health to make “aging clocks” that tell us how old we really are and how fast we age. In 2021, researchers from the Buck Institute for Research on Aging and the Stanford University School of Medicine created an inflammatory-aging clock that is better at predicting immunity, frailty, and hidden heart problems that could turn into serious problems.

That information fits with other recent research that found that centenarians—a rare population of individuals who reach 100 years or more and experience delays in aging-related diseases and mortality—exhibit unique immune cell compositions and gene activity patterns. Researchers from Tufts Medical Center, Boston University, and Boston Medical Center suggested that these traits may help explain why their immune systems are stronger and age-related diseases start later in life. This suggests that centenarians’ immune systems are still working well into old age, but more research is needed to confirm these findings.

NAD+ can preserve blood stem cells during aging

Blood stem cells, also called hematopoietic stem cells, are found in our bone marrow and make up the immune system. They make all of our red blood cells and immune cells. Because of this, your red blood cells and immune cells will probably stay young too if your blood stem cells do.

To find a way to stop blood stem cells from getting old, Dr. Chen and her colleagues started to look into a fascinating link between the metabolism of blood stem cells and getting old. They found that young people keep low levels of an enzyme called CD38 that breaks down NAD+, which is an important metabolite. Because of this, the researchers looked into how levels of CD38 affected blood stem cells in both young and old mice.

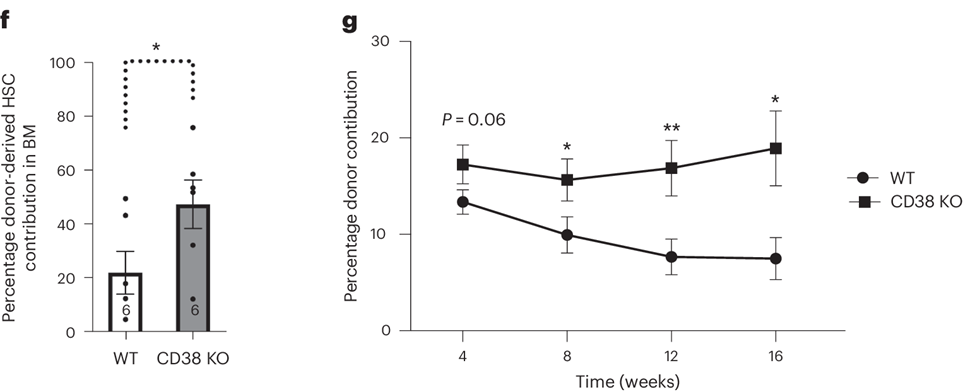

To see how levels of CD38 affect maintaining an immune system in young mice, the researchers took young mice that had their immune systems wiped out and then transplanted blood stem cells from donors either with or without CD38. Blood stem cells from young donor mice did much worse in terms of survival, health, and replication when CD38 was turned off than when it was not; in other words, those that did have active CD38, and therefore likely lower NAD+ levels, did better. Blood stem cells from young donor mice with CD38, and thus likely low levels of NAD+, performed much better at rebuilding the immune systems of mice whose immune systems had been destroyed.

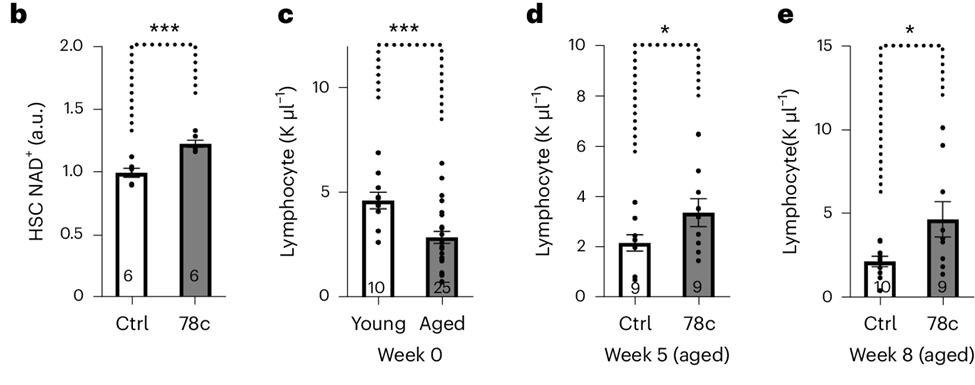

But when Dr. Chen and her team looked at older mice, basically the opposite happened. They discovered that older mice with high CD38 levels and low NAD+ levels had blood stem cells that aged more quickly. When they looked at aged mice that had been modified or treated with drugs to inactivate CD38, they discovered that they had higher NAD+ levels, lower oxidative stress, and better blood stem cell function, all of which reversed aging-related immune system defects.

A question of timing

Overall, these results show that fine-tuned CD38 gene activity is important for keeping blood stem cells working and stopping immune cells from getting worse with age. These results are important for medicine because they open the door for therapies that target the NAD+ metabolic checkpoint to make blood stem cells live longer and be stronger. Based on the findings of Chen and colleagues’ study, you shouldn’t just raise NAD+ levels whenever you want to.

Keep in mind that higher levels of NAD+ did not seem to help blood stem cells at all stages of life. In fact, they seemed to hurt the blood stem cells of young mice. Increasing NAD+ levels only helped the number, survival, and function of blood stem cells in old mice. This finding is important because figuring out if the blood stem cells are at an age where high levels of NAD+ are good for them instead of bad for them could be key to the success of this strategy in keeping human blood stem cells from getting old. An interesting next step would be to investigate how immune cells from humans, which can be easily collected from blood samples across a biological age spectrum, react to NAD+.