Key Points:

- Feeding mice a high-protein diet leads to accelerated metabolic aging, which can be prevented by restoring NAD+ levels.

- The high-protein diet induces the accumulation of age-promoting cells, which can also be prevented by restoring NAD+ levels.

- We discuss how much protein to consume for the purposes of slowing or delaying aging, particularly muscle aging.

Having a lean physique doesn’t always equate to better metabolic health. While consuming more protein can improve body composition by reducing fat and increasing muscle, it may also accelerate metabolic aging. According to a new study published in Aging Cell, feeding mice too much protein leads to insulin resistance.

High Protein Leads to Insulin Resistance that Can Be Reversed

Insulin resistance is a significantly overlooked metabolic condition, affecting approximately 1 in 3 Americans. Due to its silent nature, insulin resistance often goes undiagnosed. Still, insulin resistance is associated with the increased risk of age-related conditions like diabetes and heart disease.

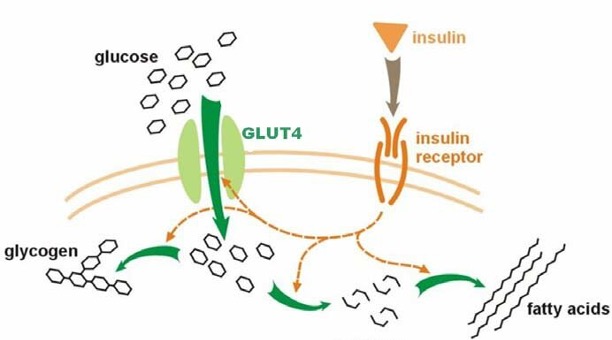

The Biology of Insulin Resistance

When we consume carbohydrates, they are broken down into glucose, which enters the bloodstream. In response to elevated blood glucose levels, our pancreas secretes the hormone insulin. Normally, when insulin binds to cells, glucose is transported into the cells. Glucose is then utilized to generate the cellular energy needed for our cells to function and survive.

In the case of insulin resistance, our cells become resistant to the effects of insulin. When insulin binds to insulin-resistant cells, less glucose is transported into the cells. Without sufficient levels of glucose, our cells cannot make as much energy. A lack of energy promotes impairments associated with aging, such as mitochondrial dysfunction and low NAD+ levels.

Boosting NAD+ Prevents High Protein-Induced Insulin Resistance

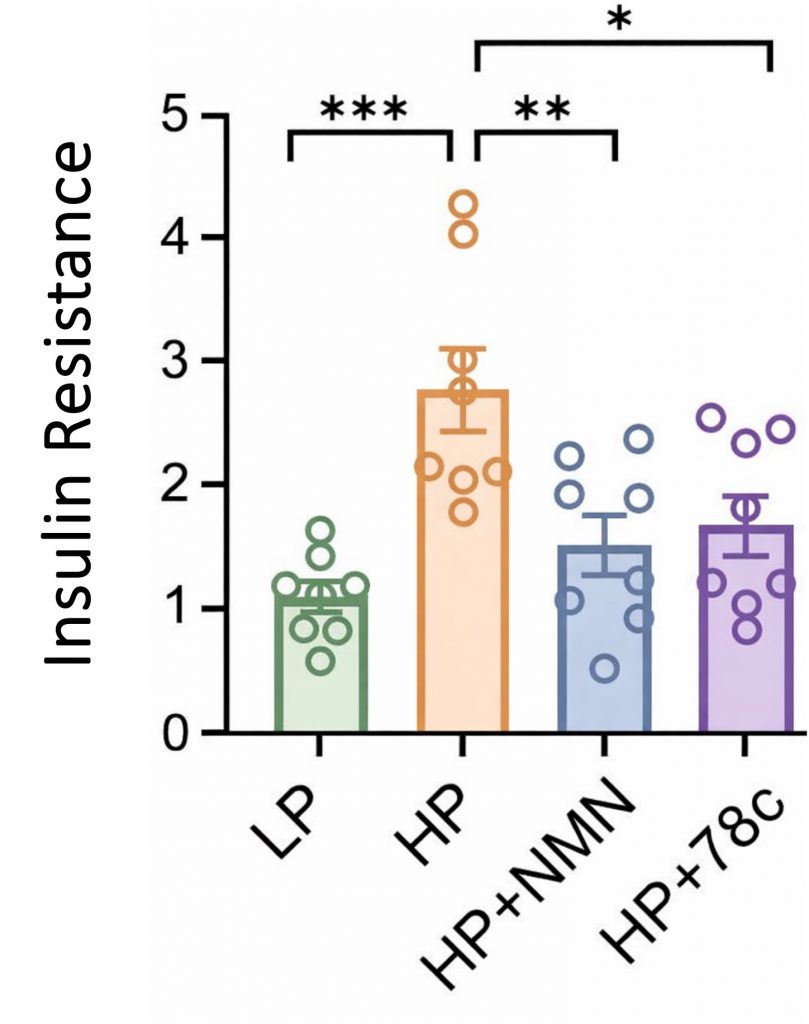

In the new Aging Cell study, researchers found that feeding mice a high-protein diet leads to insulin resistance. Moreover, the high-protein diet lowered fat tissue NAD+ levels. NAD+ is a vital molecule that helps maintain mitochondrial function and metabolic health. NAD+ precursors like NMN (nicotinamide mononucleotide) are known to restore NAD+ levels.

Remarkably, NMN supplementation prevented the insulin resistance induced by the high-protein diet. Furthermore, a molecule called 78c, which inhibits the breakdown of NAD+ (by blocking CD38), also prevented the insulin resistance. These findings suggest that boosting NAD+ can counteract high-protein diet-induced insulin resistance.

With age, we tend to gain fat and lose muscle, which contributes to metabolic defects like insulin resistance. The researchers found that the high-protein diet mitigated age-related fat gain in mice, suggesting improvements in body composition. However, since the aged mice still had insulin resistance, these findings demonstrate that leanness (not having excess fat while maintaining adequate muscle mass) does not always correlate with metabolic health.

High Protein Leads to Cellular Senescence that Can Be Reversed

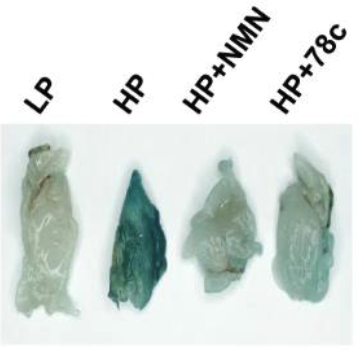

As we age, our body accumulates senescent cells, which contribute to widespread chronic inflammation. This chronic inflammation is a major driver of insulin resistance. Interestingly, the researchers reported an increase in cellular senescence within the fat tissue of mice fed a high-protein diet, suggesting that high protein intake induces cellular senescence.

Moreover, restoring NAD+ levels with either NMN or 78c was shown to prevent the increase in cellular senescence. Together, these findings suggest that consuming too much protein can promote insulin resistance by triggering cellular senescence and inflammation. Furthermore, the cellular senescence cascade may be prevented, at least partially, by restoring NAD+ levels in fat tissue.

In addition to the increase in senescent fat cells, the insulin-resistant aged mice exhibited signs of mitochondrial dysfunction and elevated inflammation. Both the mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation were largely prevented by supplementation with NMN or 78c, suggesting that restoring NAD+ levels improves cellular health and counteracts multiple drivers of aging.

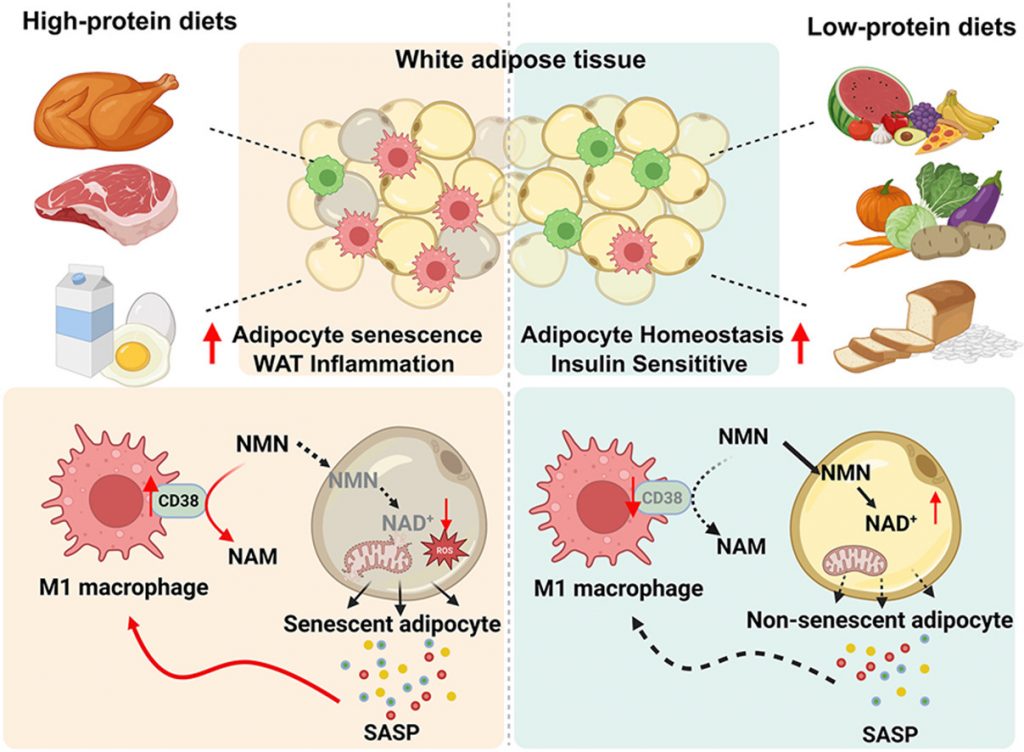

High Protein Lowers NAD+ by Activating Pro-Inflammatory Immune Cells

Through further experimentation, the researchers found that fat tissue NAD+ levels were reduced in mice due to an enzyme called CD38. CD38 breaks down NAD+, leading to NAD+ depletion. According to the researchers’ model, high protein intake induces cellular senescence in fat tissue. Senescent fat cells release molecules known as the SASP (senescence-associated secretory phenotype), which includes pro-inflammatory molecules.

The SASP recruits immune cells, such as macrophages, which carry the CD38 enzyme. In turn, the CD38-equipped immune cells break down NAD+ and lower NAD+ levels. NAD+ depletion triggers mitochondrial dysfunction, more senescence, and more inflammation, all contributing to insulin resistance. On the other hand, low protein reduces senescent fat cells and prevents CD38-rich immune cells from depleting NAD+.

How Much Protein Is Too Much?

In the study, the mice fed a high-protein diet consumed 56% of their total calories per day from protein. This means that more than half the food they consumed per day was from protein. In contrast, the low-protein diet mice consumed only 9% of their calories from protein, which coincides with the recommended daily intake.

However, the authors say:

“It is noteworthy that metabolic rates and nutrient demands differ across species; therefore, the threshold effect of protein intake in humans may not be directly extrapolated from rodent models. The precise upper limit of safe daily protein intake in humans thus remains to be established through long-term, large-scale clinical investigations.”

With that said, 56% of an organism’s energy intake from protein is very high. To put this into perspective, bodybuilders can consume up to 40% of their calories from protein, which is considered high. In contrast, the average American consumes around 15% of their calories from protein.

Biology is About Balance

In biology, too much or too little of something can be problematic. Homeostasis, the body’s ability to maintain balance despite external changes, is crucial in promoting health and longevity.

Protein restriction is associated with prolonged lifespan. However, adequate protein intake is necessary to maintain muscle mass and insulin sensitivity (the opposite of insulin resistance). Moreover, severe age-related muscle loss, called sarcopenia, is associated with a shorter lifespan. Thus, it would seem that consuming either too little or too much protein can be problematic.

The Right Amount of Protein

For maintaining muscle mass with age, practicing physician and longevity expert Peter Attia, MD, recommends consuming about 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight. Ideally, about 30 to 40 grams of protein should be consumed with each meal to promote protein synthesis throughout the day. For building muscle, consuming adequate protein should be accompanied by resistance training (e.g., weightlifting, calisthenics, and swimming).

Protein supplementation can help with achieving adequate protein intake, but it is not necessary. Animal-based foods, such as eggs, dairy, and meat, are good sources of protein. Consuming lean meats and low-fat dairy products is recommended to reduce saturated fat intake. Too much saturated fat, which is considered unhealthy fat, increases LDL cholesterol and is associated with an increased risk of heart disease.

Plant-based foods, such as legumes (e.g., lentils, chickpeas, peanuts, and soybeans), nuts, and whole grains, are also a good source of protein. Usually, a higher volume of plant-based foods will need to be consumed to achieve the same amount of protein as animal-based foods. Unlike animal-based foods, plant-based foods contain fiber. Thus, a balance of both animal-based and plant-based foods may be the best way to achieve sufficient protein intake, as limiting saturated fat and consuming adequate levels of fiber counteract cardiovascular aging.