Key Points:

- Older individuals who perform exceptionally well on cognitive tests are more likely to have larger mACCs, whereas patients with neurodegenerative disorders tend to have smaller or dysfunctional mACCs.

- Growing the mACC appears to involve performing challenging tasks that one does not wish to do, which may be achieved by developing a strong will.

“The [mACC] is smaller in obese people; it gets bigger when they diet. It’s larger in athletes, it’s especially large or grows larger in people that see themselves as challenged and overcome some challenge. And in people that live a very long time, this area keeps its size.” — Andrew Huberman, Ph.D.

Apathy — a lack of motivation, goal-directed behavior, and emotional responsiveness — opposes tenacity — persistence in the face of challenge. New research suggests that engaging in one over the other can determine whether we succumb to age-related brain disease.

The research shows that the brains of a small group of older individuals called “superagers” may age exceptionally well due to their increased tenacity. While the cognitive capacity of most older individuals declines with age, superagers exhibit the cognitive performance of middle-aged or even young adults. On the other hand, apathy is often observed in older individuals with neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

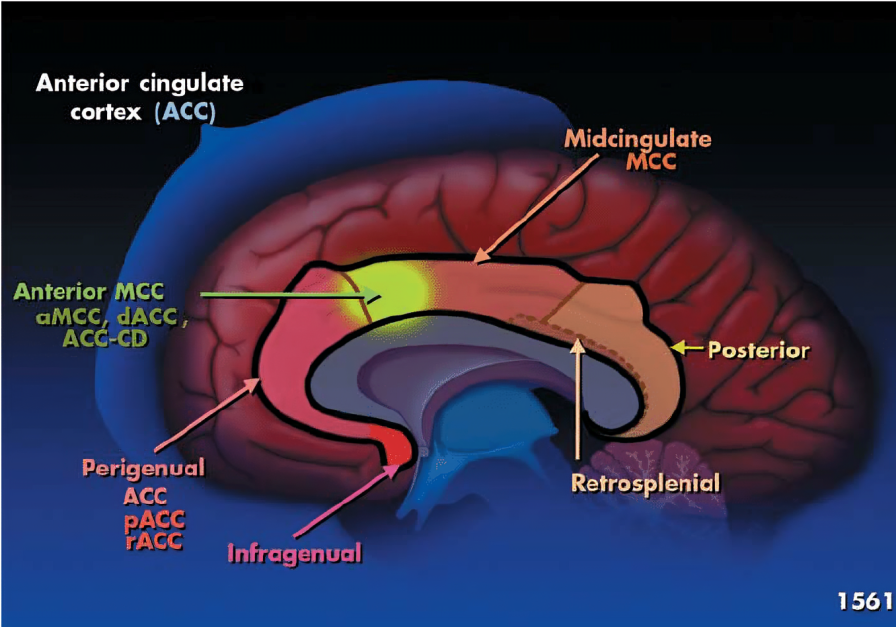

What sets superagers apart from typical older adults is a region of the brain called the aMCC. Individuals who exhibit apathy, such as depressed individuals or those with neurodegenerative disorders, tend to have smaller and dysregulated aMCCs, whereas those who exhibit tenacity such as high-achievers and superagers tend to have larger or more connected aMCCs.

Scientists propose that the aMCC acts as a central communication hub within the brain, where it integrates information from many other regions, such as those involved in decision making, motivation, and attention.

“Due to its position as a network hub, the aMCC can synchronize information from diverse systems in order to guide behavior… However, the effectiveness of aMCC computations are likely to vary between individuals, particularly in situations when the cost of effort is high, and rewards are uncertain or deferred. Under these circumstances, some will demonstrate tenacity and persist while others may simply quit.” — Touroutoglou and colleagues from Harvard and Northwestern University.

Whether tenacity and greater aMCC function can be preserved across a lifespan to result in successful aging remains an open question. Still, a conversation between neuroscientist Dr. Andrew Huberman and former Navy SEAL David Goggins suggests that the aMCC can be trained through the power of will.

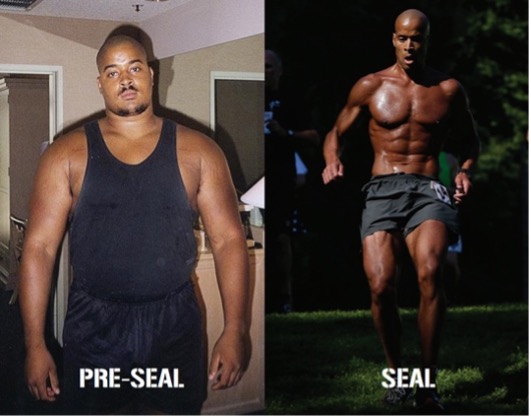

In a clip from the Huberman Lab Podcast called How to Build Willpower | David Goggins & Dr. Andrew Huberman, Huberman reveals that he waited until his discussion with David Goggins to share what he learned about the aMCC. This is because Goggins is known for his tenacity and self-discipline, using his willpower to transform himself into a Navy SEAL.

In the clip, Huberman and Goggins discuss how the best way to grow the aMCC is to do things they don’t want to. To put it another way, Touroutoglou and colleagues say,

“The aMCC appears to encode not only the value of a reward but also the cost of the effort required to obtain it. This effort may take the form of increased cognitive control, which is frequently experienced as aversive. Indeed, activity of the aMCC region during difficult tasks is positively correlated with a subjective sense of frustration, as well as desire to avoid the task.”

Goggins has had multiple knee surgeries and was told that he would never run again. Despite this advice, the pain, and the fact that it’s “the one thing he hates to do more than anything else in the world,” he runs a minimum of 12 miles every morning. In this way, Goggins is exemplary of doing something one would rather avoid.

And what would Goggins say is the best way to overcome aversive challenges and grow the mACC? He would say there are no special tricks or protocols, it’s just a matter of doing it. In his words,

“There is no f***ing lifehack. To grow [the mACC], how do you grow it? Do it, and do it, and do it and do it.”

Do it through sheer willpower. Indeed, taking into account the fact that superagers have a larger mACC, Huberman says,

“In many ways, scientists are starting to think of the [mACC] not just as one of the seats of willpower, but perhaps actually the seat of the will to live.”