Key Points:

- Researchers used NMN and a small molecule called 78c to enhance CAR-T cells, which improved survival and control of tumors in mice.

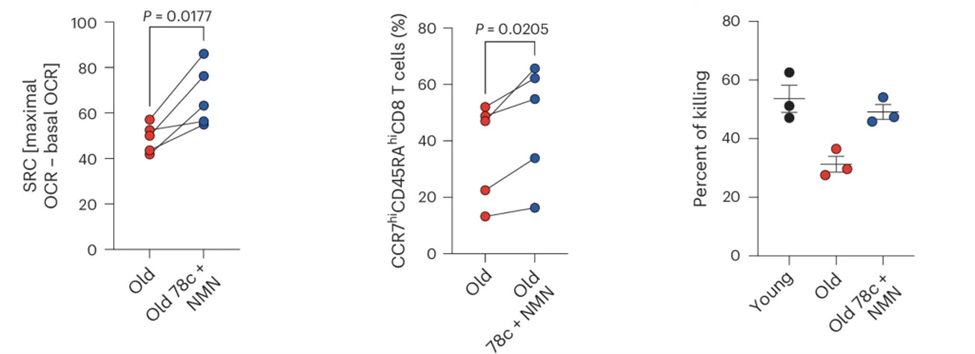

- Anti-cancer CAR-T cells from older people treated with NMN and 78c displayed improved cancer-killing abilities.

When it comes to cancer, aging has serious consequences. The risk of cancer and the likelihood that even the latest cancer treatments will fail increase with age. For younger patients, CAR-T cell therapy, which trains the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells, has shown great promise, but not so much for elderly patients. That is why Swiss researchers looked into how aging makes CAR-T cell therapy less effective and how to get things working in older patients as they do in younger ones.

A new study published in Nature Cancer reveals that CAR-T cells from older patients lose their ability to treat cancer because the aging-dependent decline in levels of NAD+, a critical cellular metabolite, leads to the production of the cell’s energy centers, mitochondria, to fizzle out. The culprit? The culprit is an elevated level of an NAD+-destroying enzyme, which increases with age. The researchers found that increasing NAD⁺ levels in older CAR-T cells can completely refresh their energy use, ability to grow, and cancer-fighting power. Researchers demonstrated this reversal in both mouse and human CAR-T models. By nailing down the root of why CAR-T cell therapy becomes less effective with aging, this study could help the CAR-T therapies finally deliver on their promise for older patients with cancer.

The study was performed by researchers at the University of Lausanne, Geneva University Hospitals, Agora Cancer Research Center, Swiss Cancer Center Léman (SCCL), and University of Geneva.

What Is CAR-T Cell Therapy?

CAR-T cell therapy was put on the map a bit over a decade ago in part due to the remarkable story of Emily Whitehead. In 2012, Emily was 7 years old and had a blood cancer that outbattled every treatment provided. When the odds of her survival looked pretty grim, doctors and researchers at the University of Pennsylvania decided to try out an experimental treatment called CAR-T cell therapy. Following CAR-T therapy, Emily’s cancer went into complete remission.

The “T” in CAR-T stands for T cells, a type of immune cell that can kill cancer cells. But that ability is dependent on the T cell’s ability to recognize cancer cells, typically through structures that sit on the cell surface of only cancer cells. The “CAR” part is where the magic happens—it is basically a way to upload information, kind of like in The Matrix, but instead of learning how to fly a helicopter, it instantly equips T cells with the tools to lock onto the cancer-specific structures and to kill the cancer cells.

Currently, CAR-T cell therapy typically relies on T cells from the cancer patient, who, regardless of age, is not usually in optimal health; consequently, the T cells are often also compromised. T cells from cancer patients tend to lose their “stem-like” qualities that help them grow and last a long time after being given to patients. Why this happens is what the researchers examined in this study.

CAR-Ts Need NAD

What the researchers found is that older T cells have problems with their metabolism, including less active mitochondria, lower ability to produce energy when needed, and smaller amounts of mitochondria. But what was intriguing was that these defects correlate with elevated levels of CD38, an enzyme that eats up NAD+, which is essential for mitochondrial function.

That finding led the researchers to see what happened if they could boost NAD+ levels in the CAR T cells. To do so, they used both a precursor to NAD+ called NMN (nicotinamide mononucleotide) and an inhibitor of the NAD+-degrading enzyme called CD38. With this approach, the researchers successfully brought NAD+ levels back to normal in older CAR-T cells during their growth outside the body. The technique also improved how well the mitochondria worked, helped the CAR T cells regain their “stem-like” state, and resulted in better survival and control of tumors after being transferred into mice. Notably, this effect was specific to aged T cells—young CAR-T cells did not benefit from the NAD+ intervention, underscoring the age-dependence of the defect.

To see if these findings could translate from mice to humans, the researchers examined CAR-T cells derived from both healthy young and elderly human donors, as well as individuals with melanoma. Aged human CAR-T cells also had lower NAD+ levels, less effective mitochondrial function, and a loss of a “stem-like” state. As with the mice, when the CAR-T cells from older people were treated with NMN and the CD38 blocker, these features were reversed, restoring their cancer-killing functionality, albeit in a lab dish.

The present study suggests that NAD+ precursors alone may not be sufficient in aged individuals, especially when CD38 expression is high. Instead, a dual approach—replenishing NAD+ while blocking its degradation—may be required. The success of combining NMN with CD38 inhibition in aged T cells offers a roadmap for boosting immune function in older patients.

Broader Implications: Beyond CAR-T

These findings not only identify a key metabolic barrier to CAR-T cell therapy in older patients but also offer a promising solution to overcome it. As the field moves toward more personalized and age-inclusive cancer treatments, targeting NAD+ metabolism may prove essential to unleashing the full potential of cellular therapies in aging populations.

The findings have implications that go beyond CAR-T therapy. Aging is the leading risk factor for cancer, and the immune system—especially T cells—is known to degrade with age. This study indicates that a decrease in NAD levels may be a significant factor contributing to the weakening of the immune system with age, which in turn affects the body’s response to cancer and its treatments. Accordingly, future human trials will be necessary to unravel whether combining NMN with 78c enhances the anti-tumor effects of CAR-T therapy in cancer patients.