Highlights:

- Restricting caloric intake by 14% prevents the shrinkage of the thymus, an immune system organ that deteriorates with aging.

- The immune system of fat tissue is less inflammatory in calorically restricted participants.

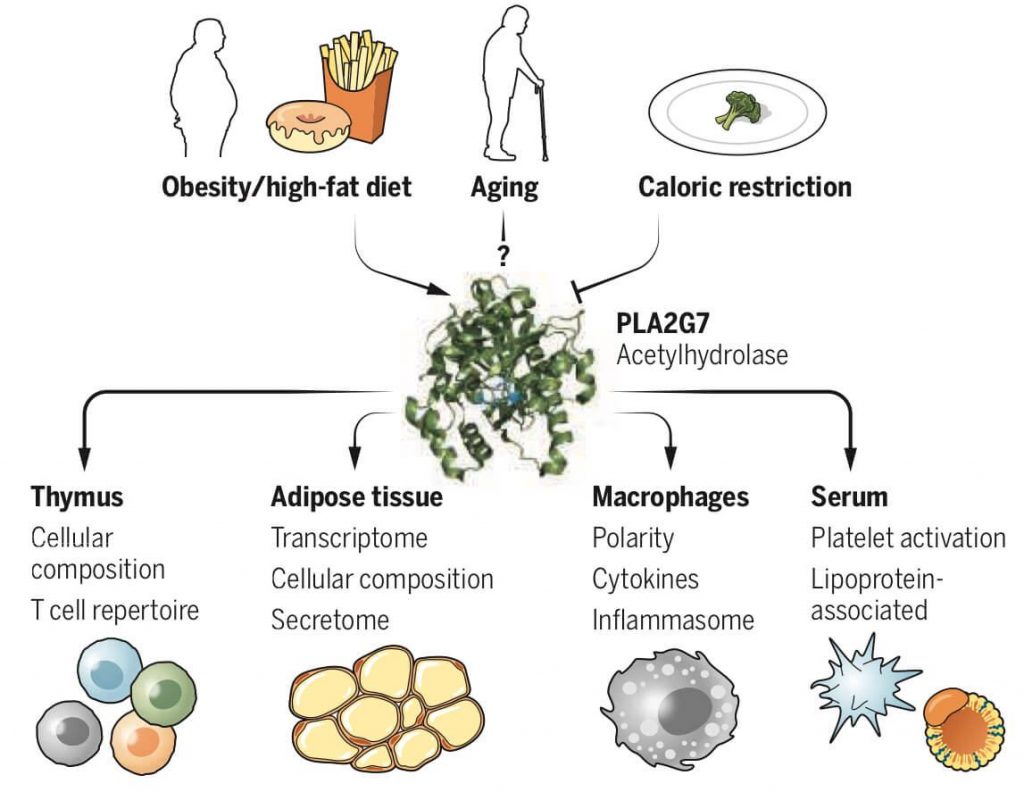

- A gene called PLA2G7 mediates the benefits of caloric restriction and is a potential mimetic of caloric restriction.

Whether eating fewer calories makes us live longer is an open question. While caloric restriction – reducing caloric intake without malnourishment – increases the lifespan of rodents, logistical complications make this difficult to determine in humans. This might be circumvented by finding the molecular levers that mimic caloric restriction (CR) in humans.

The Comprehensive Assessment of Long-term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy (CALERIE) clinical trial was designed to test CR’s long-term (2 years) effects in people. As reported in Science, Spadaro and colleagues from the Yale School of Medicine studied a subset of CALERIE participants that did 12% CR for two years, finding that CR increased thymus volume and reduced inflammation. They also found that a gene called PLA2G7 was an important mediator of these processes.

“These findings demonstrate that PLA2G7 is one of the drivers of the effects of calorie restriction,” says Vishwa Deep Dixit, the senior author of the study. “Identifying these drivers helps us understand how the metabolic system and the immune system talk to each other, which can point us to potential targets that can improve immune function, reduce inflammation, and potentially even enhance healthy lifespan.”

The CALERIE Clinical Trial

The participants of Spadaro and colleagues’ study consisted of 26 males and 6 females in their 20’s to 40’s from the CALERIE clinical trial. Of the 32 participants, 14 were of healthy weight (BMI: 18.5 – 24.9) and 18 were overweight (BMI: 25 – 29.9). Although the goal of the CALERIE study was to have the participants reduce their calorie intake by 25%, they ended up reducing their calories by about 14% over 2 years.

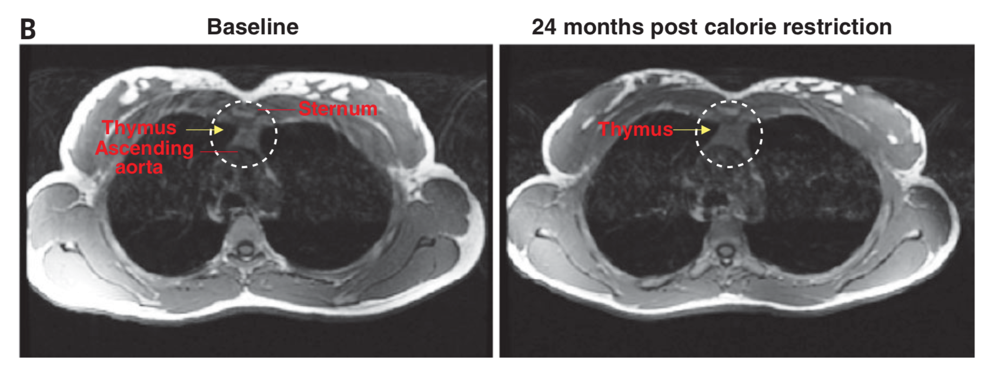

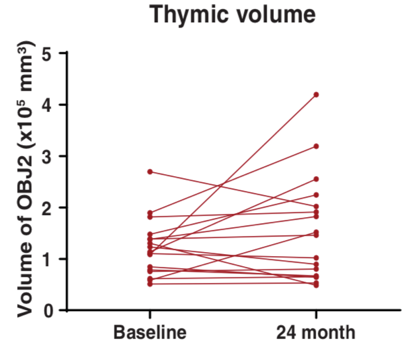

To search for anatomical changes in the immune system thymus organ in response to CR, the Yale scientists took MRI measurements of the thymus from each participant before and after 2 years of CR. The researchers also examined how CR changed gene activity in fat tissue. Based on their findings, the researchers studied a gene called Pla2g7 in mice.

CR Maintains Thymus Size

In rodents, extension of lifespan by CR has been associated with maintaining white blood cell production from the thymus. The thymus is an immune system gland that specifically produces white blood cells. Interestingly, aging of the thymus precedes the aging of other organs, with increased fat accumulation and loss white blood cell production. “As we get older, we begin to feel the absence of new [immune] cells because the ones we have left aren’t great at fighting new pathogens,” says Dixit. “That’s one of the reasons why elderly people are at greater risk for illness.”

Spadaro and colleagues investigated the thymus’s size using MRI, which showed that the thymus increased in size (mass and volume) in response to CR. “The fact that this organ can be rejuvenated is, in my view, stunning because there is very little evidence of that happening in humans,” Dixit says. “That this is even possible is very exciting.”

CR Improves Fat Tissue Metabolism

When calories are restricted, the body switches from utilizing glucose to utilizing fat as energy, which leads to fat loss. As the body adapts to CR, the immune system also adapts by modulating fat tissue function. These changes could have beneficial effects on longevity and quality of life. To determine how CR may improve the inflammatory profile of fat, Spadaro and colleagues measured genes from the abdominal fat tissue of participants. They found that gene activity changed after one year of CR and was maintained into the second year. The changes were not the same as in rodents but similar to those that occur after bariatric surgery or in response to consistent physical activity.

Specific changes in gene activity from human fat tissue in response to CR included genes associated with insulin signaling, suggesting enhanced insulin sensitivity. CR also increased genes associated with ketone body transport and longevity. Overall, the changes in gene activity indicated that CR elicits an anti-inflammatory effect that may improve fat tissue metabolism. “We found remarkable changes in the gene expression of adipose tissue after one year that were sustained through year two,” says Dixit. “This revealed some genes that were implicated in extending life in animals but also unique calorie restriction-mimicking targets that may improve metabolic and anti-inflammatory response in humans.”

The PLA2G7 Gene

Since one of the genes inhibited by CR in fat tissue was PLA2G7 in participants, Spadaro and colleagues investigated this gene further in mice. In mice with genetically deleted Pla2g7 (mouse version of human PLA2G7), immune system activation was reduced. These mice were also partially protected from a high-fat diet-induced weight gain, increased fat, and fatty liver disease.

Chronic whole-body inflammation during aging is associated with age-related functional decline. To study this, Spadaro and colleagues measured changes in gene activity in aged (analogous to 70 year old humans) mice without Pla2g7. Deletion of Pla2g7 in aged mice decreased inflammation, particularly the inflammation associated with visceral fat tissue.

Inflammation has been implicated in the age-related shrinkage of the thymus. The Yale researchers showed that deleting Pla2g7 in aged mice prevented this from happening. Based on these mouse studies, the authors propose that the reduction of PLA2G7 by CR in humans might contribute to better fat tissue metabolism, lower inflammation, and reduced thymus shrinkage.

(Spadaro et al., 2022 | Science) The PLA2G7 Mediates Inflammatory Response. Caloric restriction inhibits the PLA2G7 gene leading to increased thymus function and decreased inflammation.

PLA2G7 Therapy?

Spadaro and colleagues show that just a 14% caloric deficit can reduce fat and enhance the function of the thymus in healthy middle-aged individuals. Overall, the findings demonstrate that CR changes an entire gene activity pattern, promoting immune function and reducing inflammation. Since chronic inflammation is associated with age-related diseases, it seems likely that reducing inflammation with CR could increase lifespan.

“There’s so much debate about what type of diet is better — low carbohydrates or fat, increased protein, intermittent fasting, etc. — and I think time will tell which of these are important,” says Dixit. “But CALERIE is a very well-controlled study that shows a simple reduction in calories, and no specific diet, has a remarkable effect in terms of biology and shifting the immuno-metabolic state in a direction that’s protective of human health. So from a public health standpoint, I think it gives hope.”

This study reveals the importance of PLA2G7 as a mediator of many of the changes that occur in response to CR.

“We found that reducing PLA2G7 in mice yielded benefits that were similar to what we saw with calorie restriction in humans,” said Olga Spadaro, a former research scientist at the Yale School of Medicine and lead author of the study.

Now that the FDA has approved technologies for transferring specific genes into humans, we can begin thinking about PLA2G7 as a potential candidate for gene therapy. Instead of having to eat less through CR, we may be able to use PLA2G7 therapy as a mimetic for CR in the future.