Key Points:

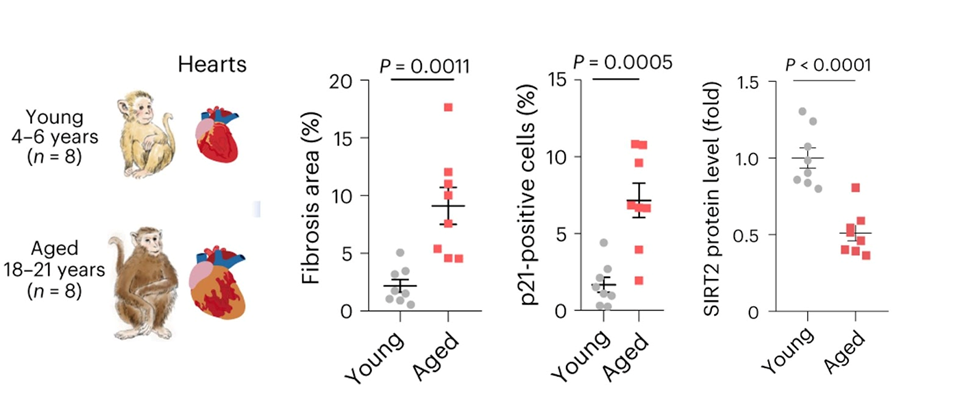

- Aging Cynomolgus monkeys had less sirtuin activity (SIRT2) in their hearts compared to young Cynomolgus monkeys.

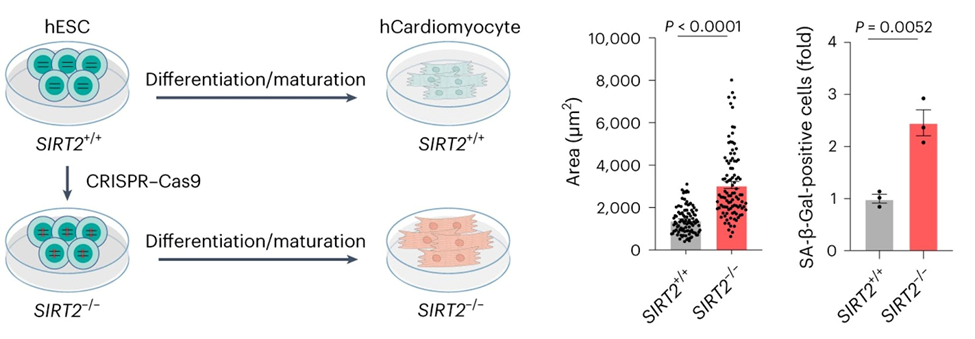

- When SIRT2 production was blocked in human heart cells grown in cell culture, the cells began to age more rapidly and showed signs of impaired energy metabolism.

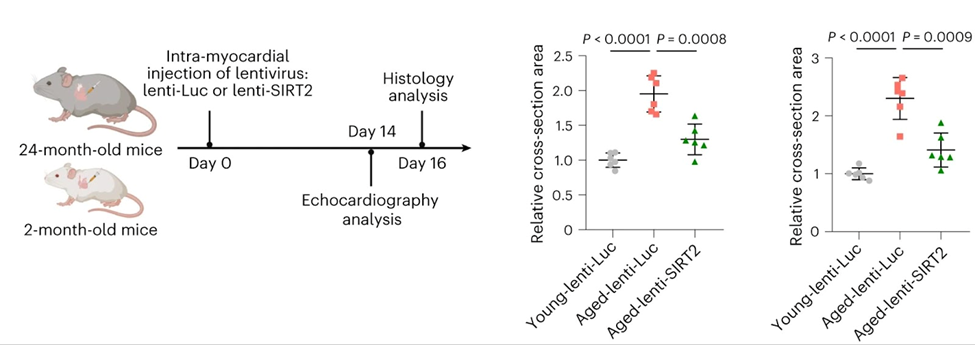

- Mice with age-related heart dysfunction saw improvements in heart health and function when SIRT2 levels were boosted.

Scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Beijing Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine have found that SIRT2 is an enzyme involved in monkey heart aging. Lowering SIRT2 levels made heart cells (cardiomyocytes) from human stem cells act a lot like old monkey hearts that were formed naturally. In contrast, raising the levels of SIRT2 in mice that were naturally old made their hearts work better, suggesting that SIRT2 signaling may control cardioprotective effects. These findings, published in Nature Aging, pave the way for developing therapeutics that target SIRT2 to combat heart aging and the heart diseases that come with it.

Dissecting Heart Aging from Disease

Around 5% of adults over the age of 20 have heart disease, making it the leading cause of death. Also, it seems that getting older is a big risk factor for heart disease since 80% of heart disease deaths happen to adults over the age of 65. Heart diseases and changes in the structure and function of the heart are more common in older people. But it is hard to tell the difference between the processes that cause normal heart aging and those that cause disease. To find ways to treat heart problems and disorders that happen before heart disease, we need to understand how the heart naturally ages.

SIRT2 Prevents Cardiac Aging in Primates

For this study, a team of researchers under the direction of Jing Qu, Weiqi Zhang, and Guang-Hui Liu analyzed the hearts of aged Cynomolgus monkeys. The Chinese researchers found a number of important characteristics and biological processes that change as the heart naturally ages. For example, the heart shows higher levels of scarring and inflammation, and heart cells get bigger and become locked into a non-replicative state (known as senescence) in aged monkey hearts. In addition, their analysis showed that levels of an enzyme known as SIRT2 were considerably lower in the aged monkey heart.

To see if SIRT2 plays a role in human heart aging, the researchers made heart cells from stem cells that could not make SIRT2. They found that human heart cells without SIRT2 recapitulated many of the characteristics seen in aged monkey heart cells, such as the increased size and and senescence. Also, when the researchers blocked downstream components that are typically activated by SIRT2, they observed that the heart cells began to degenerate.

For the study of whether adding SIRT2 could help slow down or stop heart aging, researchers used a gene therapy approach to generate SIRT2 in the hearts of old mice. Compared to old mice that were given placebo gene therapy, those that were given gene therapy to make more SIRT2 had better heart function and less heart aging. Of note, the amount of blood the heart could pump and the contractile ability of the aged hearts improved with the administration of the SIRT2-producing virus. These results add to earlier research that showed that mice lacking SIRT2 also have hearts that get bigger with age, along with more inflammatory cells and scarring. These findings show that SIRT2 is an important cardioprotective factor in heart aging and provide direct evidence that increasing SIRT2 slows down or stops heart aging in mice.

More research needs to be done on the possible effects of SIRT2 on certain tissues that are important for healthy aging in humans. Also, more in-depth research is needed to show how SIRT2 changes throughout an adult’s life. This will help figure out how early these molecular changes can be found and whether they really happen before the functional and structural changes seen in aging hearts, or if they are just a reflection (and not the cause) of the heart problems that happen.

Taken together, this study identifies SIRT2 as a potential therapeutic target against human cardiac aging and aging-related cardiovascular diseases. Two potential methods of doing this in humans would be to find drugs that can increase levels of SIRT2 or mimic SIRT2 activity. Another method would be similar to the viral approach the authors used in mice, which is a version of gene therapy (though viruses are not necessarily required). Also, because SIRT2 needs NAD+ to work and NAD+ levels are thought to drop with age, the addition of NAD+ precursors may work synergistically with a gene therapy that raises SIRT2 levels.

Also, longitudinal studies are needed to help us understand the differences between tissues because SIRT2 expression may change at different times in different organs. These studies keep track of the same people over long periods of time, usually years or decades. Inhibiting SIRT2 seems to protect against neurodegeneration, which is especially true in the brain. In the heart, SIRT2 is needed to keep cells from aging, but in the brain, SIRT causes aging. So, gene therapies that activate SIRT2 would need to specifically target the heart and avoid the brain to work.