Key Points:

- The NAD+ precursor NRH increases NAD+ levels in immune cells when other NAD+ precursors (NAM, NMN, and NR) do not.

- More than NMN, NRH promotes the activation of genes associated with inflammation in mouse immune cells.

- NRH and to a lesser degree NMN also promote inflammation in human-derived immune cells.

When can too much of a good thing be bad? Some substances like sugar can be beneficial in small amounts, as it gives us energy and tastes delicious. However, too much sugar can be harmful, as it could lead to diabetes and heart disease. NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) – a vital molecule that keeps our cells running – can be beneficial, alleviating age-related ailments and increasing longevity. However, a new study shows that NAD+ could be harmful, as it promotes inflammation.

In an article published in Frontiers of Immunology, Chini and colleagues from the Mayo Clinic report that NRH boosts NAD+ levels in mouse and human immune cells far more than other NAD+ precursors. But in both mouse and human immune cells, NRH promotes inflammation. These findings clarify some controversies over whether NAD+ promotes inflammation, which it seems to do in immune cells. This inflammation-promoting capability isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as NRH could be used to modulate the immune response against tumor growth.

Boosting NAD+ to Higher Levels

The microscopic machinery of our cells is oiled with the movement of NAD+, a small molecule needed to metabolize our food into cellular energy and push forward hundreds of reactions that keep the cell machine running. NAD+ is such a vital molecule that without it, our cells would die. Accordingly, the decline of NAD+, which occurs with aging, is associated with nearly all age-related diseases.

NAD+ is continuously being recycled through the process of degradation and synthesis. Precursors of NAD+, such as NAM (nicotinamide), NMN (nicotinamide mononucleotide), NR (nicotinamide riboside), and even vitamin B3 are used as the molecular pieces needed to build NAD+ molecules. When ingested or injected directly into the bloodstream, these NAD+ precursors increase NAD+ to varying levels.

A relatively new NAD+ precursor, NRH (dihydronicotinamide riboside), has been shown to boost NAD+ faster and to a much higher level than NR and NMN. While NMN and NR are degraded outside the cell, it is believed that NRH remains unscathed. This makes it a powerful tool for understanding the physiological consequences of extreme NAD+ boosting. Chini and colleagues are the first to describe the effect of NRH on immune cells.

NRH but not other NAD+ Precursors Boosts NAD+ In Mouse Immune Cells

Immune cells harbor a multitude of enzymes that can either synthesize or degrade NAD+. Many of these enzymes are active during inflammatory disease processes and appear to play a role in the function of different immune cells. Since NAD+ is involved in many immune system processes, it seems to play a role in regulating the immune system. However, just how NAD+ metabolism is involved in immune function and inflammatory disease is unclear.

To investigate the effect of NRH on immune cells, Chini and colleagues used cultured cells. Cultured cells are cells that are grown and maintained in a dish. The benefit of using cultured cells is that they can easily be manipulated with different drugs and conditions. In their first set of experiments, the researchers used cultured immune cells derived from the bone marrow of mice (bone marrow-derived macrophages).

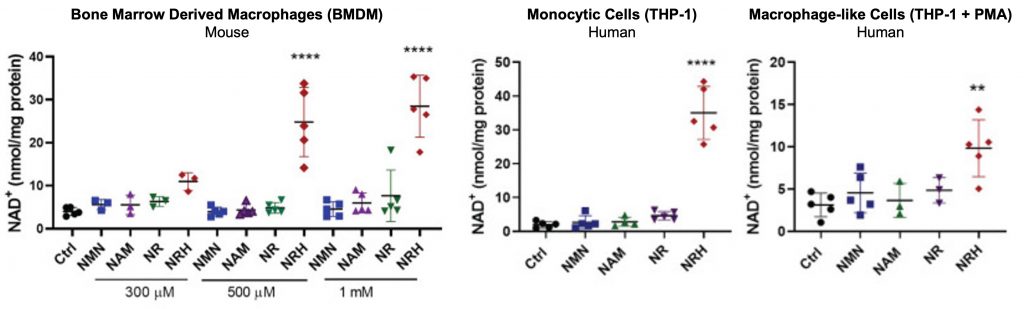

Treatment of the mouse immune cells with NRH induced a dose-dependent increase in NAD+ levels up to sevenfold higher than with the other NAD+ precursors. NMN, NR, and NAM did not significantly increase NAD+ levels. Additionally, NRH boosted NAD+ for at least 16 hours, whereas the other precursors did not. These results demonstrate that NRH, not other NAD+ precursors, boosts NAD+ in mouse immune cells for extended periods.

(Chini et al., 2022 | Frontiers of Immunology) Only NRH boosts NAD+ levels in cultured mouse and human immune cells. Doses of 500 µM NRH – but not NMN, NAM, or NR – boost NAD+ levels in (left) mouse bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM), (center) human monocytes (THP-1), and (right) human macrophage-like cells (THP-1 + PMA).

NRH Increases Inflammation in Mouse Immune Cells

After confirming the NAD+ boosting potency of NRH, Chini and colleagues examined whether NRH treatment increased inflammation in mouse immune cells by measuring mRNA levels. Messenger RNA, called mRNA for short, provides the template for specific genes to be made into their corresponding proteins. Quantities of mRNA molecules are often used as a proxy for the protein concentration within cells. The researchers found that NRH treatment increased the mRNA levels of genes associated with immune cell activation and inflammation. NMN treatment also increased the mRNA levels of genes associated with inflammation, but these levels were not as high. Together, these results demonstrate that NRH and NMN induce inflammation in mouse immune cells.

NRH Increases Inflammation in Human Immune Cells

To further explore the role of NRH and other precursors on boosting NAD+ and regulating immune cells, Chini and colleagues determined the effect of NRH on human immune cells called THP-1 monocytes – white blood cells precursors to macrophages. When THP-1 monocytes are treated with a compound called PMA (phorbol myristate acetate) they take on the characteristics of macrophages – white blood cells that are mobilized during an inflammatory response. These macrophages are similar to the immune cells used in the mouse experiments above. The results showed that only NRH and not the other NAD+ precursors could increase NAD+ levels in these cells, regaurdless of macrophage activation.

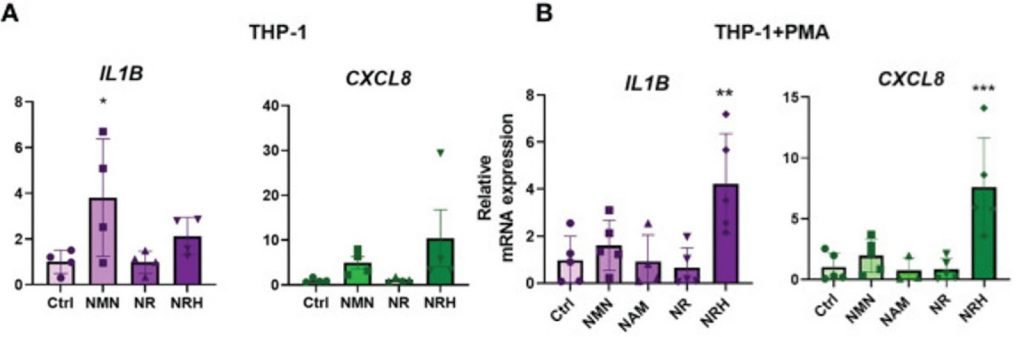

The Mayo Clinic scientists next measured the mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory genes in activated and non-activated THP-1 cells. In the THP-1 cells not treated with PMA (non-activated), NMN and not the other precursors increased the mRNA levels of an inflammatory mediator called IL1B. In THP-1 cells treated with PMA (macrophage activation), NRH but not the other precursors increased the mRNA levels of multuipel pro-inflammatory genes. These results demonstrate that NRH, and to a lesser extent NMN promote inflammation in human immune cells, while only NRH boosts NAD+ in human immune cells.

(Chini et al., 2022 | Frontiers of Immunology) Some NAD+ precursors promote inflammation in human immune cells. All four graphs show mRNA levels in human immune cells (THP-1 monocytes). (A) In untreated THP-1 cells, only NMN increases inflammatory mediator IL1B but not CXL8. (B) In response to PMA, which activates THP-1 cells to become macrophage-like, only NRH increases inflammatory mediators IL1B and CXL8.

NRH-Induced Inflammation for Suppressing Tumor Growth

The findings of Chini and colleagues show that the NAD+ precursor, NRH is one of the only known precursors capable of boosting NAD+ in immune cells. This large increase in NAD+ followed by NRH treatment leads to the activation of genes associated with inflammation. While chronic inflammation can lead to disease, transient inflammation can be beneficial. Some immune cells and the inflammation they cause can slow the progression of tumor growth. Therefore, by understanding the behavior of these immune cells and how they are modulated by NAD+, boosting NAD+ with NRH could potentially be used as an immunotherapy to treat cancer.

Can Boosting NAD+ be Bad?

When can too much of a good thing be bad? Boosting NAD+ to promote inflammation transiently can be good for suppressing tumor growth, but what about boosting NAD+ regularly? Studies have shown that boosting NAD+ with precursors like NMN does not lead to side effects in humans. Also, many animal studies have shown that boosting NAD+ is beneficial and can actually reduce inflammation in aged models. However, most of these studies did not use NRH to boost NAD+, so to understand if the NAD+ boosting effects of NRH outweigh the inflammatory effects, these studies would need to be repeated with NRH. It could be that NRH boost NAD+ to such high levels that inflammation is activated where it otherwise would not be with less potent NAD+ precursors, in which case too much NAD+ could be bad.